May 2026

Waiting for Lippman

In hindsight, my only regret is that I wasn't there the night that it rained tampons.

Perhaps more explanation is needed.

Remember just last month, when I offered my advice on how to talk to an author? There should have been a seventh caution: Don't ask about film rights. Here's the reason. The vast majority of books do not get made into films or television shows. Some get optioned, but most of those will not make it to the small or large screen. And of those book-into-film projects that are produced, the results are often mixed. For every Mystic River and Adaptation, there's . . . well, fill in the blank. Still, Hollywood is an iteration of the American dream and as long as that dream lives, the question will persist.

More challenging than the question, however, is the subsequent advice when I admit that my work has yet to be optioned. "Have you sent your books to Barry Levinson?" Years ago, I put three paperbacks in a manila folder and mailed them to his production company without note or explanation, just so I could henceforth say yes. "Have you thought about HBO?" I think about HBO constantly, but that's another story. "Doesn't Hollywood buy any old piece of crap?" (Truly, the question is often framed in just those terms.) Yes, I think that's in the Declaration of Independence -- the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of a packaging deal with CAA.

As of April, however, I have to learn a new shtick: Frances McDormand has optioned Every Secret Thing. Here are my answers to the next round of questions: No, No, No, and No. ("Are you rich now?" "Will you write the screenplay?" "Do you have casting approval?" "Will you ask for a cameo?") This is the beginning of a long journey and, strange as it might sound, it's not my journey anymore. The next leg belongs to McDormand, an actor I admire extravagantly, and her vision of Every Secret Thing. An option is, by definition, much more than a check. It's a choice, a chance, an opportunity, a right to exercise power.

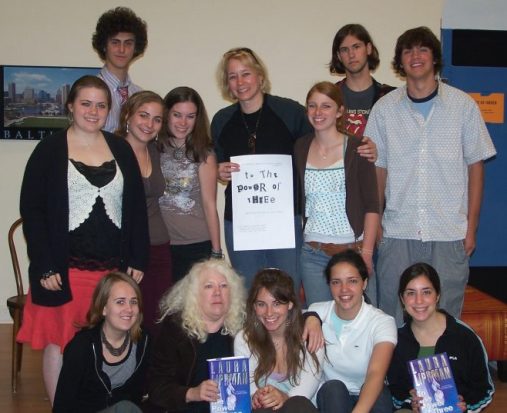

Given the vagaries of the film business, it may be years, if ever, before I see my work on the big screen. But, as it happens, I've already seen one of my books onstage. Seven Hills School, outside Cincinnati, adapted To the Power of Three for its spring show. It played to sold-out audiences April 28 and 29th, and even had a packed house for the dress rehearsal April 27th. And I was there in the front row, next to Beth Tindall, aka Cincinnati Media.

This journey had started only a few months earlier, when I was contacted by the students' teacher, Patty Flanigan, asking if they might adapt the novel. We worked out an agreement that would protect my future rights to the book and I happily ceded all control. Would I mind, Patty asked via e-mail, if the shooting, the novel's central event, took place off school property, as Seven Hills principal insisted. No problem. What about name changes, or the fact that Josie Patel was now Josie Kashka? Go for it. I told Patty repeatedly: Whatever you need to do, I'll endorse.

From the beginning, I knew I had to attend, although we tried to keep this a secret from the cast, a reverse Guffman if you will. By intermission, however, word had spread, although the actors later assured me that they didn't find it unnerving. "But it's good we didn't know too far in advance," one said. "That would have been too stressful."

As for my emotions? It was simply one of the most thrilling nights of my life. Patty and her students made smart choices in streamlining an event-filled book, concentrating on the teenagers and trimming the parts that dealt with the adults' angst and anxiety. No one knows the material better than I -- actually, it's possible that Kelsey Truman, who played Perri, has me beat -- but I was on the edge of my chair when the final scenes unfolded, crying silently. Tears of joy or sorrow? Both, I think. Joy for the fact that this material spoke so strongly to the very people it portrayed -- teenagers in an elite school. And sorrow for the senseless tragedy that envelopes three former best friends.

The next day, when I went to speak to the students, I learned just how hard they had fought to stage the play. The production had almost been cancelled three times and they had persevered, according to their teacher, only because of their civilized but impassioned arguments for the material. Psychologists were brought in to counsel them. There were fears that they would imitate their counterparts in the play. Gee, I wondered, if simply playing these parts could cause such trauma, what must it do to the person who creates them? "That's one of the points we made!" they said gleefully.

The show must go on, according to the old saying, but most troupers have never been up against school authorities. This show went on without a key bit of evidence from the crime scene. It was decreed, late in the rehearsal period, that there could be no mention of a used tampon, a prominent detail in the novel. The backstage crew, in good-natured protest, threw feminine hygiene products from the light booth the night of the first tech run.

It's impossible to single out any performer, especially given the fact that I saw only one cast. (There were two casts, and is it vain of this old Harander to hope they called themselves "Crunchy" and "Creamy," a la the production of Peter Pan in Three?) People kept saying that it was nice of me to be there, that it meant so much to the students, but I have to think it meant far more to me. I had dared to try and tell their story, and they were generous enough to validate my version of it. In class Friday morning, I told them I had been moved to write Three, in part, because teenagers are so often treated as the national id, the root of everything run amok in our culture. In our prurient fretting about their computer habits and sex lives and drunk driving, adults let themselves off the hook for similarly bad behavior. As the old song says, the kids are all right - especially those I met at Seven Hills School. Which means the parents must be doing all right, too.

So thank you to: Patty Flanigan, Katherine Cummins, Chesa Greggs, Sophia Beckwith, Amy Sherman, Kelsey Truman, Brooke Howard, Benjamin Greenberg, Rob Pasternak, JP Brubaker, Gabriel Kalubi, Megan Owen, Sarah-Margaret Gibson, Marisa Steinmanis, Meg Ganulin, Talia Amatulli, Torie Gehrig, Valerie Runge, Tyler Troendle, Henry Antenen, Mac Lewin, Lennie Cottrell, Kevin McGraw, Drew Westcott, Weslie Coleman, Medha Gupta, Nevin Rao, Eric Osborne, Michael Makris, Jessalyn Reid, Sean Malley, Stewart Mills, Ammon Hollister, Luke White, Douglas Wulsin, Margaret Cummins,Devin Arbenz, Lucy Portman, Alex Ferree, Luke Beckwith, Rachel White, Zoe Pochobradsky, Hilary Sehring, Zoe Teets, Alex Shifman, Katie Hamilton, Michelle Corey, Blair Lanier, Stephanie Moulton, Peter Dumbadze, Daniel Filardo, Erin Jenkins, Jono Lawson, Greg Sheer and Michael Vanoy.

What does Emily say at the end of Our Town? "Oh earth, you are too wonderful for anybody to realize you."

Books and Coming Attractions

Pistol Poets has found a new home. But there are always more good books in need. So drop me a line and who knows what might result? Meanwhile, check in here next month for the complete NO GOOD DEEDS tour. Reviews and reader reaction continue to be gratifyingly positive. ("Following on the heels of Lippman's haunting standalone To the Power of Three, Tess Monaghan is back in this ninth entry of the award-winning series . . . Things get really sticky until the highly satisfying and surprising ending. Strongly recommended for all libraries." Library Journal.)